My

Father in Spain ©

The

most exciting and the most interesting story I ever heard was the story of my

father's season in Madrid in the spring summer of nineteen thirty seven; Madrid

besieged. There he, my dad, tangled with Hemingway. There he fell in love with

Capa's girl. "Look after her, Ted," Capa said. Ted was with Gerda Taro

that day, when she died. And Bethune, Norman Bethune, who would impact the world,

the course of history… the Brigade asked Ted to look into what was happening

with Bethune: there were rumours. Beth said, "In that case you be the Unit's

political officer, the commissar." Months later Ted would send Bethune back

to Canada. It's quite a story.

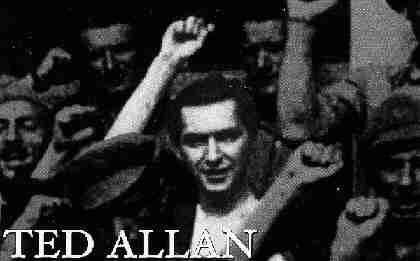

My father, Ted

Allan, made several attempts at writing his autobiography. "Look," he

said, "if I die before I finish this - I keep it here in this desk drawer

- Finish it!"

Many parts of the autobiography

needed expanding, but the story of Ted's adventure in Spain was almost all there

in one or other of his drafts and notes. So here is my take, my assemblage of

"My Father in Spain."

1936.

Ted's just twenty, soon be twenty one, and he's off to Spain to stop Franco, to

fight fascism.

"The

Canadian Party, in the persons of Fred Rose, had agreed to send me to Spain as

correspondent for the party newspaper, the Daily Clarion. I got my passport, and

a number of farewell parties took place to wish me bon voyage. I traveled first

to Toronto to meet with Leslie Morris, the editor of the paper. The Montreal comrades

had forgotten to check with Leslie Morris, and in the meanwhile Leslie had made

arrangements for Jean Watts to act as the paper's correspondent. Watts had come

into their office just the day before I got to Toronto. Embarrassment and apologies

all round, but I was screwed.

I

decided, to hell with it, I'd volunteer for the International Brigade. Fred Rose,

our party chief, insisted that I be a good boy and continue my work as the Montreal

correspondent of the Clarion.

I

said if he didn't okay my volunteering, I'd enlist anyway, without the Party's

permission. He warned me I could be expelled if I acted without Party permission.

I

said I'd risk the expulsion. Nothing and no one was going to stop me going to

Spain. I was going to participate directly in that war one way or another. If

I was to die, fine I'd die right there in Spain, but I wasn't planning to get

killed. I was planning to avoid the shells and bombs and to do some good work

broadcasting from Madrid and writing freelance for newspapers and magazines.

"If

you join the Brigade you'll be in a bloody trench, not broadcasting from Madrid!"

shouted Freddy.

"Okay,"

I said.

Freddy

finally gave in and I was off to Spain, still under party discipline, enlisted

in the International Brigade."

Let

us cut to many weeks later, the town of Albacete, head-quarters of the International

Brigade: the new volunteers are being inducted.

"That

afternoon we were assembled in the bull ring in Albacete. ... There were several

hundred of us. New recruits. An officer stood on an improvised wooden platform

and shouted at us with a heavy Chicago accent. He bellowed a welcome and announced

that he would now assign us to our units. He asked if anyone could drive a truck.

Several recruits spoke out or raised their hands. "Okay, you're in transport."

He marched them over to a table at the side of the arena where they would be signed

into their unit. "Okay, who knows how to operate short wave radio?"

No takers. "Okay, anyone have any medical training?" A few volunteers

selected themselves out of the trenches and moved to the side. "Okay, who

can drive a motorcycle?" A handful raised their hands. "Okay, you'll

be dispatch riders. Okay. The rest of you are infantry. You'll be the heroes."

We were marched over to a table where the rifles

would be issued, our names taken and filed, next of kin... Everyone now handed

over their passport for safe keeping. That was like a door closing. The doom of

the trenches began to drag at my stomach.

When

we reached the table we were reviewed one by one by the Brigade officer in command.

He introduced himself to each of us - very civilized, Peter Kerrigan, a Colonel

in the Brigade and the Political Commissar of the British battalion. Colonel Kerrigan

inquired briefly of each of us about our background. I told him I was a writer

and reporter, that I'd worked for the Clarion in Montreal, and that I was now

a correspondent for the Federated Press. He made a guttural noise, an "ah",

and paused. "We've lost lot of writers this last month. Cauldwell, Ralph

Fox. Do you know their work?"

I nodded.

"We need journalists," Kerrigan said.

"I may transfer you to Madrid to work as a correspondent for the Brigade."

"But I can't leave my comrades," I protested.

All of me meant this, and all of me feared that he might take me at my word.

He nodded his head tiredly. "Your protest is

noted. Believe me, I'd send you to the front if I though that was where you would

serve us best. Come and see me this evening. We will arrange your transfer."

That evening in the Brigade Headquarters I

had dinner with Kerrigan and others in command. We were joined by George Marion,

the correspondent for the London "Daily Worker" who stopped off in Albacete

on his way from Madrid to Valencia. Discovering that I was a Canadian and from

Montreal he spoke of the rumours that had been circulating in Madrid concerning

Bethune's Blood Transfusion Unit. The rumour ran that Bethune was drinking heavily

and fighting with the Spanish doctors. The morale in the unit was said to be low.

"Do you know Bethune?" Kerrigan asked

me, for he knew we were both from Montreal.

"I

know him well. We are good friends. In fact he asked me to come and work with

him here if I had any spare time. That was when

I thought I was coming over as a reporter."

"Fine.

I want you to see Bethune in Madrid. Place yourself at his disposal. You're to

investigate what's going on in the Blood Transfusion Unit and report back to the

Brigade. Report to comrade Gallo directly." Gallo was the Head Political

Officer of the International Brigade. Kerrigan took out a folded sheet of paper

from the breast pocket of his uniform. "Here is your Safe Conduct pass. Find

yourself transportation to Madrid. Report to brigade headquarters there. Good

luck, and, oh, Ted! finish your dinner first and do stay for a cup of tea."

When

the Second Republic was founded in 1931, Spain was polarized between right wing

National Front and the left wing Popular Front. Tensions built. During the governments

of the left there were burnings of churches, and abortive military coups. During

the government of the right there were general strikes and fighting in the streets

between the fascist Falange and militants of the left. An up rising of miners

in Asturias was bloodily suppressed.

The

elections of February the 16th 1936 saw a narrow victory for the Popular Front.

The fascist National Front openly appealed to the military to save Spain from

Marxism. On July 17th 1936 the military revolted. The insurrection was quickly

consolidated in colonial Morocco and in extensive areas in metropolitan Spain.

Catalonia and the Basque Provinces were loyal to the government, for the Republic

guaranteed their autonomy. In Madrid and Barcelona the rank and file of the armed

forces, aided by the militias of the workers, defeated the officers. Spain was

divided in two: the Republic holding the industrial zones; the Nationalist holding

the food producing areas.

The

core of the Nationalist army were the battle hardened African corps under the

command of General Franco. At first their advance was irresistible. By November

the 7th 1936 Franco's armies were at the gates of Madrid. The loyalist government

fled to Valencia. Madrid was expected to fall. Only the enthusiasm of the people

of Madrid and their militias, and a remnant of the loyalist army, were left to

resist Nationalist onslaught. Arturo Barea writes, "That morning the outlying

workers' district on the other side of Segovia Bridge had been attacked by the

fascists. My sister, her husband, and her nine children had fled together with

all the neighbours, crossing the bridge under shellfire. Now the Fascist troops

were entrenched on the other bank of the river and advancing into the Casa de

Campo, the University City. From the window of the censorship office in the Telefonica

building I heard people marching out towards the enemy, shouting and singing,

cars racing past with screeching motor horns, and behind the life of the street

I could hear the noise of the attack, rifles, machine guns, mortars, guns, and

bombs. The Gran Via, the wide street in which the Telefonica lies, led to the

front in a straight line. The front came nearer. We heard its advance. Towards

two in the morning somebody brought the news that the Fascists had crossed three

bridges over the Manzanares river, the Segovia, Toledo, and King's Bridges, and

that there was hand-to-hand fighting on the campus of the City University a kilometer

away."

But

here, in the University City, the Fascists were held. The next day saw the first

engagement of the foreign volunteers, the International Brigades. The lines of

the loyalist resistance became firm. The Fascists had been stopped. The siege

of Madrid began.

The

siege of Madrid would last for two years. During this time the centre of Madrid

was shelled regularly. The Telefonica building, a modest sky scrapper, twelve

stories high, became a primary target. In the spring of 1937 Ted Allan would make

his regular radio broadcasts to North America form this target.

In

February 1937 the Nationalist renewed their offensive for Madrid with a flanking

attack on the southeastern approaches to Madrid. The loyalist and the International

Brigades halted the enemy advance on the Jarama at a terrible price. This is the

backdrop for Ted's arrival in Madrid in February 1937.

Meanwhile Ted's friend

and mentor, Norman Bethune had left for Spain months before. Bethune arrived in

Madrid on the 3rd of November, just before the siege. Over the ensuing weeks Bethune

devised and began to organise the "Servicio Canadiense de Transfusion de

Sangre" to deliver blood transfusions on the battlefront. The Spanish Red

Cross, the Socorro Rojo, provided Bethune with premises to operate from, a 15

room luxuriously furnished house at 36 Principe de Vergara, a gracious boulevard

in a rich suburb. Many of the rich had fled to the Fascist held lands, and the

rich suburbs of Madrid were the safest part of the city. The Fascists did not

shell the rich or their property.

The

Red Cross also provided Bethune with a staff for the unit including a couple of

Spanish doctors and nurses. Meanwhile Bethune flew to Paris and then to London

to outfit the unit. He bought two station-wagons and fitted them with generators,

refrigerators and sterilization units. He returned to Madrid in early December

to set up the Unit, which went into operation in January. It was an instant success,

and a great morale booster. It gave the people of Madrid, the Madrilenos, another

way of participated directly in the resistance, by giving blood. And, along with

the International Brigades, it symbolised foreign support. But already in February

their were rumours of serious problems with morale in the Blood Transfusion Unit.

And

later, I might mention, much later, in China, organizing the medical services

for Mao's revolutionary forces fighting the Japanese, Bethune would become, posthumously,

perhaps the most famous person in China, after Mao tse Tung himself.

However,

now, having left 1937 and Spain, let's travel back to Montreal a few years earlier

to Ted's story.

"I

happened to be visiting my mother one evening in March of 1934, about a month

after my eighteenth birthday. I was very full of myself for I had recently, for

the first time, had a short story published.

The

telephone rang and my mother answered. "Its a Dr. Bethune wants to speak

to some Ted Allan." (Ted had just adopted the name, Ted Allan.)

I

swallowed, and taking the telephone's ear piece, I managed to say hello. A cheerful,

vigorous, baritone voice, speaking very clearly, said, "Norman Bethune here.

Miriam Kennedy gave me your phone number. I loved your story in New Frontier.

Just had to call and tell you. Pure gold. Is it true you're only eighteen?"

I grunted an affirmation, and Bethune continued, "I'm having a party this

coming Saturday evening. A lot of my friends will be there. I'm celebrating my

forty-forth birthday."

I gulped that I'd

be glad to come, thanked him, and concentrated on getting the address in my head

correctly. He said he was looking forward to meeting me, and hung up.

Bethune's

Beaver Hall Hill apartment was up three flights of stairs. The first thing one

noticed on entering the room were the children's paintings on the walls. Book

shelves covered two further walls from floor to ceiling. As I entered the room

Bethune made his way to greet me through the crowd, both arms outstretched. A

handshake and a quick hug. I was mesmerised.

"Before

I introduce you around," Bethune said, "there is something I want you

to do first." He led me off up a little hallway to a door. He opened the

door to the bathroom. On one bathroom wall hung all his diplomas. And the wall

facing the door was covered in handprints. By each handprint was a signature.

A pan of blue paint stood on a high stool. Bethune led me into the bathroom, took

my left hand and placed it in the bowl, in the paint. Then he directed my palm

to the wall, pressed my hand against the wall and said, "Sign it."

"Ted Allan," I wrote.

"You

are now numbered amongst my special friends," said Beth.

Our age difference

made me shy, but in retrospect I realise I had found a surrogate father.

From

Ted's notes dated February 10, 1937:

"I

arrived in Madrid exhausted. Came by truck from Albacete. No light. Difficult

driving at night.

Beth greeted me warmly, hugging

me, embracing me, laughing at the way I looked in my International Brigade uniform.

I couldn't stop my sudden weeping. With in minutes he had me sitting at a huge

dinning table: coffee, rolls, and terrible tasting margarine! Then he said, "You'll

be the political commissar of the unit."

My

mouth fell open. I had a sudden terrible feeling. Should I tell him that I had

come because the Brigade wanted me to report on the Blood Transfusion Unit because

of all the stories circulating? Finally I got it out, blushing. He laughed. "Great!"

he said. "Somebody should find out what's going on. I could use some help.

I hereby renew our recent appointment as Political Commissar of the Spanish-Canadian

Blood Transfusion Unit. The moment you feel you know what's going on here please

report in detail to the International Brigade, the Party, anybody you want to.

Feel better?"

I did. Then Jim came in (Jean

Watts whom I'd met on the boat across). We hugged. Beth announced I was now Political

Commissar of the unit. Jim said, "Hah!" And then, "Well... congratulations."

Later she told me she didn't like Beth, whispering

to me in the hallway, "Can't stand him!"

"Why?"

I asked astonished.

"Tell you when I have a chance."

I

suspected that he doesn't find her attractive and this is killing her.

I'm

still haunted by the memory of that dead child I pulled out of the ruins in Albacete.

The town in flames. The noise. The nightmare of it. Me holding the dead child

and weeping and screaming. And then that peculiar sensation of seeing the words

"Something happened to me once and I wonder what it is." As if I was

that child, dead. I told Beth about it. He said, "Write it quickly before

you forget. Just get the notes down." There

are huge lines outside the Servicio Building to give blood. I watched the Unit

in operation. It's very impressive.

Note: faces,

enthusiasm, each donor gets food (don't be cynical).

I

slept like a log. Slept, slept, slept, in a beautiful room Beth gave me off the

corridor.

I must write a dispatch for Federated

Press about the Albacete bombardment. And do a piece on the Blood Transfusion

Service. I'm now a Political Commissar with the rank of Colonel. I wonder what

the International Brigade will say to this. It's funny. Beth's done it half as

a joke.

I'll have to call a meeting of the Party

members.

…

UNDATED.

1937. Damn it. I hate that man sometimes! He got drunk again last night and smashed

the door shut so hard the glass broke. He's infuriated at Culebras and his nasty,

devious manner, and at Culebras' sister. All very well. I can't blame him for

being angry, but to get so damned drunk and scream at Culebras like that in front

of everyone!

I told Gallo about the drinking.

Gallo is a lovely man. Being Italian and more tolerant (is that the reason) he

said he can understand Beth drinking because of the strain. All the rumours of

trouble in the Unit come from Beth losing his temper with Culebras and his sister.

Beth wants them out, but Culebras is a Party member, and the Spanish Party is

not clear about the reasons for the arguments. How does one tell them Culebras

is a prick? I think Culebras feels he should be head of the unit, because he's

a Spaniard. But Beth conceived it, invented it, created it! The whole idea of

bringing blood to the battlefield like a milk delivery system is Beth's,

I hated him last night because of his drunkenness.

It reminds me of my damned Papa. Febr.

28, 1937. Rumours of some bloody battle on the Jarama front. That's where my comrades

are, John, Milty, Dave, all the guys with me on the boat and the barracks at Albacete.

I feel guilty living the life of a Medical Worker, Foreign Correspondent, with

them in the trenches. I spoke with Beth about it last night. He said he understood

but suggested I was doing the job I knew best how to do.

March

1, 1937. Today I love him! He's made me cry. I woke up this morning and a brand

new typewriter was beside my bed. I've been using the Unit's typewriter. Beth

had commented, "How in hell can you call yourself a writer and not have a

typewriter?"

"Ah, that's the rub,"

I had said.

Now I stared at the new typewriter

There was a note. "If you want to be a writer you need a typewriter. Love,

Beth." I couldn't believe it. I dashed out of the room, into his bedroom.

Ula was still there. Hah! I love her too. (Ula is a journalist from the Stockholm

Tagblat who came to interview Bethune a week ago. "An in depth interview,"

says Bethune.) She's a darling. She's leaving next week for Sweden. Culebras sister

will be pleased.

I was carrying the machine

with me. "Is this true?" I asked.

He

looked at me deadpan. "You need a typewriter, don't you, you ninny. One of

your own. You call yourself a writer, don't you?"

"Where

did you get such a lovely typewriter?" I asked. It was a Royal.

"Had

it sent to me from Barcelona."

I gushed

out my thanks, felt like a kid, and rushed back to the room and I am typing on

it now. Beautiful machine. I'll write some good stories on it!

Thank

you Beth. (Didn't mean a word when I said I hated you. Love yah!)

MARCH

5th. 1937. Just came back from Jarama. Photographer Geza Karpathi, and Herbert

Kline with me. Can't stand it. John, Dave, Milty and twenty others on the boat

with me, dead! All dead. Wiped out in some stupid attack. God.

MARCH 6th.

1937. Beth says I should have a little holiday. Don't want one. Feel sick. John

dead. Milty dead. Feel sick.

Beth took me for

a walk, We were very quiet. He said very little, but I loved him for being so

sensitive. I hope I come through for him. I wish he didn't drink so much and get

so angry and irascible. It scares me sometimes. In

March General Franco made another flanking move on Madrid. At Guadalajara the

International Brigades decisively defeated the motorised Italian corp that the

Nationalist had thrown into the fray, but the loyalists were unable to follow

up on their victory. The Madrid campaign remained in stalemate.

(UNDATED.)

Just got back from an area near a place called Guadalajara. Beth giving blood

transfusions to wounded, dying soldiers. He was like a mother to them. He really

cares. He's fearless. Makes me frightened the way he doesn't care about bullets,

bombs, anything. I told him he's bloody suicidal. He said, "Rubbish."

On the way there in the ambulance, with me and Henning

and Geza (taking pictures), Bethune drove into enemy territory by mistake. Damned

windshield shattered by machine gun fire. Two bullets through right over Beth's

head, and mine! I dived to the floor of the ambulance.

Henning

opened the door and jumped out. Beth leisurely brought the ambulance to a stop.

I could have killed his calmness. Geza was white with fear, and I was giggling

at him, probably hysterical. Christ, what a terrible soldier I am! I get petrified

at the sound of bombs, gunfire, any sudden noise. Henning had dived into the ditch

first, me on top of him and Geza on top of me. More machine gun bullets and a

bloody enemy tank, an Italian tank coming towards us. I couldn't believe my eyes.

And Beth? Shouting at us angrily, "Get out

of that ditch. We've got four cases of blood! Get them out!"

The

great reluctant heroes, Henning, Geza, and myself crawled out of the ditch to

help Beth carry the cases of blood into the ditch, the bloody machine gun still

at us. How in hell did he stay so calm and cool? He wasn't putting on any act,

unless being so cool under fire is an act. Henning, Geza, and I were infuriated

at him for driving us into enemy territory in the first place, and then calmly

making us look like three cowering idiots.

The

blood was safe for the moment, but the tank kept coming and I said, "Shit,

we're going to be massacred."

"Not

necessarily," Beth said. "They'll see our medical insignias (Socorro

Rojo) and just take us prisoner."

And then

from out of nowhere a Republican tank appears and then another and then another

and the Italian tank turns and skidoos.

We come

out of the ditch. Spanish soldiers surround us and cheer and help us put the blood

back into the ambulance.

And then Bethune administering

the transfusions an hour later to these badly wounded kids. God, they don't look

more than 18 or 19. They look so young, crying "Madre mi madre". Beth

putting his hand to their foreheads, giving them cigarettes.

Sometimes

I hate him. Sometimes I love him.

Ted

learned from Bethune that throughout his life Bethune might wake at night from

a nightmare, not knowing where he was, but in panic and often with a compulsion

to travel, to move somewhere, anywhere. So in Madrid, on occasion, Bethune would

drive off in the middle of the night in the one of the Unit's station wagons,

the ambulances. "Once he didn't stop until he reached Valencia. He was gone

five days without anybody knowing where he was." This behaviour did not help

the smooth running of the hospital, and put Ted, as Bethune's friend and confidant,

and Political Officer of the unit, in an awkward position.

The

main problem within the unit, however, flowed from the friction between Bethune

and the Spanish doctors. "Culebras, was a pain in the ass. He would insist

on having his afternoon siestas no matter what was going on." No emergency

would shift him from the leisurely manner he saw as his right. For Bethune such

self-indulgence was totally unacceptable. Culebras' wife work in the Unit's blood

laboratory, and his sister was a nurse with the Unit. All were members of the

Communist Party, which gave them a certain degree of tenure. They were immovable.

Bethune, however, felt the matter was more than a clash of personality or culture,

more than petty obstruction. Bethune felt that Culebras was a fascist sympathiser

and an active saboteur. But Bethune was hardly rational. He drank like a fish.

Ted could understand, but not excuse, the drunken binges. But Bethune seemed insane

when he maintained that even the mild mannered and inoffensive Dr. Gonzales was

a fascist saboteur.

Bethune

was popular with his patients and with the common people. He was viewed him as

a symbol of Internationalism. But he made enemies easily. Jean Watts told Ted

she thought Bethune was "egocentric to the extent of mania. Really quite

crazy. Completely insensitive. I hate him." Arturo Barea, the censor, describes

how "Doctor Norman Bethune, the dictatorial chief of the Canadian Blood Transfusion

Unit, came stalking into the room with his escort of lumbering, embarrassed young

helpers." Bethune had found some correspondence in German in the house on

Principe de Vergara. It turned out to be rather innocuous inconsequential letters

from some time before, but Barea says Bethune insisted on making an issue of it.

"In immaculate battle dress, his frizzy grey hair slicked back on his long,

narrow head, he stood there swaying slightly on his feet and proclaiming that

he would take these important paper - his own treasure trove - to Alvarez del

Vayo, in the blood Transfusion van."

Yes

indeed, Bethune was a handful. What was Ted to do? Nothing for the moment.

Late

in March 1937 Ted visited Valencia. Then on March the 30th, as Ted was about to

return to Madrid, Constancia de la Mora, who was in charge of the government press

bureau, asked Ted if he would mind sharing his car with an American reporter,

the correspondent for Colliers magazine, who was looking for a ride to Madrid.

The

following is from Ted's notes dated "1946", and titled "Hemingway".

"Constancia is an incredible woman.

She wrote a book that some of you may remember, "In Place of Splendour".

She was in charge of propaganda for the Spanish government. Her husband was the

head of the Spanish airforce, whatever there was of it.

Constancia

asked if I would take some reporter to Madrid. I made a face to indicate that

I was not too keen on sharing the car. She told me, "You will not be sorry

when you see her."

"In that case,

by all means," I said.

Constancia smiled,

and then frowned. "There is a man, an acquaintance of her's, to travel too."

I shrugged. "C'est la guerre."

The

next morning in the lobby of the Hotel Victoria, Constancia introduced me to Martha

Gellhorn. Martha was a very attractive young blond lady, in her mid or late twenties,

quite striking looking. She came out of a cultured and comfortable background,

highly educated, and had been working now many years as a writer and journalist.

Her latest novel, "The Trouble I've Seen", which had been published

the summer before, was highly acclaimed. I didn't know all this at the time, just

that she had a wonderful smile, beautiful hair, and a great figure. I absolutely

flipped. Constancia told me that Martha had just arrived and didn't know too much

about the war, so Constancia asked me to brief her on policy matters.

The

car arrived. The driver opened the door and a man stepped out whom Constancia

introduced to me as Sidney Franklin. Sidney was an American bullfighter with quite

a reputation in Spain. On the way to Madrid when we stopped in a village, the

word spread like wildfire. Children tagged after him, grown-ups stood about entranced,

and even the mayor came out to shake his hand. You know, he may have been the

only Jewish bullfighter in history. Sidney and Martha may have been acquaintances,

but I had my brief, to fill Martha in on the background of the war, so Sidney

sat in front seat beside our Spanish chauffeur.

Martha

and I settled in the back seat and I gave her a brief history of the war. We felt

very comfortable together, hit it off immediately, and soon found ourselves almost

sitting in each other laps, giggling and cuddling for warmth under the baleful eyes of Sidney Franklin, who turned around frequently

with a disapproving glare. It was a long trip. Martha and I spent nearly the whole

journey kissing and necking.

warmth under the baleful eyes of Sidney Franklin, who turned around frequently

with a disapproving glare. It was a long trip. Martha and I spent nearly the whole

journey kissing and necking.

When we got to

Madrid I had to go to the Blood Transfusion Unit: she had to go to the Hotel Florida.

I asked, "When will I see you?"

She

said, "Whenever you want".

I said,

"In a couple of hours."

She said,

"Fine."

So a couple of hours later

I was in her hotel room. I asked her, "Have you got the key to the door?"

The various hotels I've had been in in Madrid always needed a key to lock the

door.

She kept smiling. She said, "No."

I said, "For Christ's sake. I know you

have the key. I want to close the door."

She

kept smiling. It appeared that this door did not need a key to be locked.

So we were sitting on the bed, and there's a knock

on the door. It opens, and there's this big man I've never met, but I've seen

pictures of Ernest Hemingway. He went, "Oh!"

She

said, "Oh, come in. This is uh, Ted."

I

said "Hi."

I looked at her. He stared at me, and she said, "I'll

see you later, okay Ted?"

"Okay yeah."

May

26th, 1993. Ted is seventy seven. It is 56 years later. Ted is with his young

friend, Helen. (Is it or isn't it an affair? Helen says no.) They are recording

their conversation on tape. Ted feels the conversations are, in part, hilarious,

and that they may be able to write a comedy from this material. Much of the material,

however, is dry and serious. In the following section Ted's doing most of the

talking.

"I've also

come to the conclusion that I exude a certain kind of scent, a certain kind of

chemistry, because women and men are more influenced by smell than any other factor,

I'm convinced of it. So I must have had a powerful scent that I exuded, otherwise

I can't explain why women have found me attractive. This thought is being triggered

by what Merrily Weisborn told me this morning, that Martha Gellhorn told her when

she was interviewing her for the documentary (on Ted). Martha Gellhorn told her

that when she met me in Valencia - I was then 21 years old, she was 27 (Gerda's

age) - I was exceptionally handsome. I looked like a gypsy. My eyes were sparkling,

and she had an instant crush on me. We cuddled in the car all the way from Valencia

to Madrid. She's the woman who married Hemingway, and happens to be one of the

finest writers alive today.

She then revealed

something to Merrily that I'd forgotten, and that was that Sidney Franklin, the

bullfighter, threatened me in Madrid, and said if I saw Martha again he would

attend to me, and he scared me. It may have influenced me, coz he was a big bruiser.

Sydney Franklin and Hemingway were close friends. They had traveled to Spain together.

Bullfighting and machismo bound them. I didn't see too much of Martha, but that

was mostly because Hemingway was jealous and keeping her under lock and key.

Indeed,

we read in Kert's "Hemingway's Women" an account of Martha Gellhorn's

first days in Madrid : "After her arrival in Madrid, Ernest tried to take

charge of Martha in ways that were sometimes heavy-handed. On her second night,

during a heavy bombardment, she woke up and, seeking company, found her door locked

from the outside. She banged and shouted but to no avail. Finally, when the shelling

stopped a hotel employee unlocked the door. Who had locked it, she wondered. She

located Ernest in someone's room playing poker. He had locked it, he admitted

sheepishly, so that no man could bother her."

From Ted's notes written

in Spain, 1937: "Bethune

and I met Hemingway today. Beth and Hemingway hated each other at first sight.

But I like Martha Gellhorn. Mmm. So did Bethune. Mmm.

Met

Robert Capa and his girl friend Gerda Taro. Yum Yum. Beth and I giggled at one

another after we left them.

"Isn't she

beautiful?" I said.

"A delicious thoracic

creation," he said.

"Yum Yum,"

I said.

"Make that ditto," he said. Back

to Ted's "Hemingway" notes:

All

the correspondents used to eat in a restaurant on the Grand Via. Lunch, not dinner.

And the next day sure enough there was Hemingway and Martha sitting there. There

was every well known writer in the world around that table at the time. Everybody

was there except Shakespeare. It was incredible. And she, Martha - Hemingway was

very possessive about her. It turned out that he was expecting to marry her.

She hadn't mentioned this. Franklin had told Hemingway

that we had been necking in the back of the car, so his attitude to me, right

from the beginning, was not friendly.

I was twenty one at the time. He was in his mid

or late forties. He had not yet written "For Whom the Bells Toll", of

course, but he had been one of my heroes as a writer. I had loved his short stories

and I had loved his novels "The Sun Also Rises" and "A Farewell

to Arms". He was already world famous by this time. He was the correspondent

in Spain for the North American Newspaper Alliance and was writing marvelous stuff.

I was sending cables to the trade unions wire-service,

Federate Press. I was also just beginning to broadcast regular radio reports to

North America.

The head censor in Madrid was

a man called Arturo Barea who worked with his wife, Ilsa. Barea met with the foreign

corespondents once a week. He would refer to various dispatches he thought were

special or important and everyone would be very excited.

One

afternoon Barea started to read what he said was "one of the most vivid,

the most exciting dispatch ever written." Before he started to read we all

automatically turned to Hemingway because that description could only describe

something Hemingway had written. I thought, "What a moment. What a historic,

incredible moment."

After the first lines

three of us knew that it wasn't Hemingway's piece. Barea was reading the article

I had sent that morning describing the bombardment at Albacete, and everybody

was going, "Oh, fantastic," looking at Hemingway, and saying, "Great,"

and I thought, "Holy shit." Hemingway was trying to wave off the compliments,

"No, no!" but nobody knew. Finally when it was over they all jumped

up, "It's great. It's Fantastic. It's..." and Hemingway said, "I

didn't write it." And Barea said, "No, no! Ted Allan!" Soon

after that Hemingway asked me if he could read my short stories. I said, "Would

you?"

He said, "Yeah."

"Oh,"

I said. "I'll get them," and I got up to leave.

He

said, "Great. Bring them to the hotel"

I

ran back to the Blood Transfusion Institute and picked up the several short stories

I had with me in Spain, and ran to his room at the Florida Hotel. I gave him the

stories and I thought, "Oh God. This is fantastic. He's gonna read my stories."

I waited and waited. It took a week or so and one

day at lunch he said, in front of everybody, "I read your stories, kid."

"Yeah?"

"I

guess I don't have anything to worry about."

I

said, "Yeah, well I didn't think you'd have anything to worry about."

"Yeah," he said. "You know what you

should do with your stories?"

"Yeah,

what?"

He said, "You should put then

away for ten to twenty years, and then come back to them."

I

said, "Yeah, okay, thanks."

And this was at the lunch table with

everybody listening. I thought he was being pretty shit ass.

A few days

later I was at the Hotel Florida and there he was at the bar. "Hi. Hi, kid."

All the rest of them called him Poppa or Uncle. Bethune and I were the only ones

who called him "Mr. Hemingway."

We

both went down to the toilets to pee. As we were peeing in the urinals, the hotel

was hit by a shell. Now the Florida Hotel was hit by shells one or two times a

week. And it shook. We were peeing, and Hemingway said, "Well, one of the

good things about the shells hitting this hotel is it's getting rid of the Jews."

I said, "What do you mean, it's getting rid

of the Jews?"

"Well, I heard Herb

Kline was leaving." And he mentioned three Jewish guys who had been in the

hotel and they were leaving.

I said, "Didn't

you know I was Jewish?"

He said, "Oh

Christ, I didn't remember you were Jewish."

I

said, "Yeah, I'm Jewish."

He said,

"Oh shit." He then said to me, this was after the peeing, "Hey

kid, if you ever write a novel, I don't care what it is, I'll write a preface

for it."

I said, "Oh, great."

Later,

in New York, Ted brought Hemmingway his first novel, This Time a Better Earth.

"I gave him the novel when he

and his wife, Martha Gellhorn, were in a New York hotel. He said he'd read it

that night. When I came back next day he said, "I read it. Gerda was a whore.

I'm not writing a preface for this rubbish."

So

Martha came out with me, closed the door and said, "He's so full of shit.

He's so full of shit. I'll tell you something quick: he can't fuck. He goes in,

he's finished and boom it's over. Okay, have I made it up to you?"

I

said, "Not really."

So much for Hemingway.

A

few years into the twenty-first century I got a call from a doctoral student researching

"Canadian writing on Spanish Civil War". He wanted to discuss the possibility

of re-issuing This Time a Better Earth. I mentioned that Ted came to call

the work Next Time a Better Book.

"Oh,

I found it a page turner," he said. "You know that both Ted's book,

published in 1939, and Hemingway's Spanish Civil War book (For Whom The Bells

Toll), published in 1940, start with the hero riding in the back of a truck

coming into Spain over the Pyrennes"

told him that Hemingway had refused to write a promised preface for the novel.

"That's

interesting," he said. "There were two copies of This Time a Better

Earth in Hemingway's library when he died."

Back

in Spain, in the Civil War, Ted split his time between working with Bethune at

the Blood Transfusion Unit and living the life of a war correspondent in the besieged

city. Madrid, the centre of the world. Rubbing shoulders with Hemingway, Dos Passos:

"everyone but Shakespeare".

During

the spring Ted suggested to Gallo… Gallo was the nom du guerre of Luigi Longo

who many years later would succeed Togliati as head of the Italian Communist Party.

Gallo, as we've mentioned, was Chief Political Commissar of the International

Brigade, and Ted was reporting to him about Bethune. Ted suggested to Gallo that

he might broadcast reports from Madrid to North America. Gallo approved. This

took Ted to the Telefonica building, that landmark and target, every night in

the midnight hours so that his broadcasts would reach the East Coast of America

in the evenings.

During

this period Herbert Kline and Geza Karpathi were making a documentary of Bethune's

work, "The Heart of Spain". Meanwhile that other "publicity hound",

Hemingway, was making his documentary, "Spanish Earth." Photographers

Robert Capa and Gerda Taro (Capa's beautiful companion, whom Hemingway is reported

to have called a "femme fatale") were involved in this project. We'll

meet them later. Back

at the Blood Transfusion Unit, tension continued to grow. Two more Spanish doctors,

a haematologist, and a bacteriologist, joined the unit. With this Culebras gained

some success in his campaign to "democratise" the Institute, to achieve

more Spanish control. In practice what this amounts to was a bureaucrification,

a proliferation of rules and paper, restrictions on Bethune's freedom of action.

Bethune

responded stormily. Ted had already seen him slam a door so hard its glass window

shattered. Now he watched Bethune hurl a heavy glass ashtray across the room at

Culebras. When the innocuous Dr. Gonzales inadvertently spilled a bottle of blood,

Bethune growled, "Idiot". That's a word the Spaniard recognise, and

it had a chilling effect. Gonzales was mortified. All possibility of professional

cooperation seemed ruptured. By this time everyone else had already turned against

Bethune. Now, even for the young Ted Allan, his hero had lost most of his luster.

Ted wrote:

"Beth

and Culebras' antagonism was becoming impossible. After a few more drunken tantrums,

broken windows, thrown chairs, flung ashtrays, another episode absconding in the

night with an ambulance, I began to find myself allied with those Bethune called

"the misfits and the shits". I saw him, not as a loving mentor, but

as a drunkard and a publicity seeker. I agreed now that he must leave the Unit,

and wrote a full report, copies to the Brigade in Madrid and to the Party in Canada,

suggesting Bethune be sent back to Canada. In Spain he was a liability. At home

he could be of service speaking and raising money for the Spanish Aid Committee.

A.A. MacLeod and William Kashtan of the Canadian

Communist Party traveled to Madrid to investigate. The day that they arrived and

phoned me, Bethune, sober for a change, was planning to leave for Valencia to

buy, he said, some medical supplies. Any excuse to get away, because we all knew

there were no medical supplies in Valencia. I suggested MacLeod and Kashton come

to the Unit the following morning and be present at a meeting of the Unit's personnel

to hear it all for themselves first hand.

The

meeting next morning went its inevitable way, one speaker after the other telling

MacLeod and Kashton how impossible a man Bethune had become with his drinking

and whoring. Admittedly he had done wonderful work at the beginning, but he seemed

to have degenerated into an incurable and unpleasant alcoholic.

Finally I

took the floor. "We all know he's a son of a bitch..." I began. I didn't

get much further. Some drapes that walled off an alcove parted and, from their

folds, out stepped Bethune. He had not gone to Valencia as he had said he intended,

but had hidden that morning behind these curtains in the room where we held our

meeting. He glared at me.

"Thank you comrades

for your expressions of trust and loyalty. I appreciate it. Especially from you."

His countenance was withering. Beneath the steal of his stare, hurt and humiliation

were too painful to conceal. My shock and embarrassment left me speechless.

He turned to MacLeod and Kashton. "I am happy

to resign from the Blood Transfusion Service, but I see no advantage in returning

to Canada. I can be used here as a surgeon. I will join one of the Brigades medical

units."

MacLeod said they could discuss

all this in private. I persuaded MacLeod and Kashton that it appeared that Bethune

could not handle himself at this time in Spain; that he should be ordered home

where he could be of more use. Eventually Kashton and MacLeod persuaded, or ordered,

or in any event prevailed upon Bethune. Bethune returned to Canada to tour and

lecture promoting the Spanish cause. Ted

would go on to write the first biography of Bethune: "The Scalpel, The Sword",

published in 1952. It was a eulogy - that seemed to Ted and his collaborator to

be politically appropriate at that time - but the book troubled me. Bethune is

portrayed as a man of exceptional energy, drive, ambition, talent, intellect,

and charisma, and the moral of the biography seemed to be - seemed to me when

I first read it at the age of twenty - that if you had that exceptional talent,

energy, et cetera, why then you could make a contribution. But if you're black,

get back... I didn't like this Bethune. I felt he had nothing for me, nothing

of help to me.

Over

the years, listening, talking to my father, I got a different picture of Bethune.

I learned the details of my father's relationship with Beth, which were not then

in print. My father was, in some sense, a protégé of Bethune's.

They were almost like father and son. "He turned into my father, crazy Harry"

said Ted, "I felt that he had betrayed me." Listening to my father tell

the stories on memorable nights in his apartment in Putney above the river, looking

down through the grey to the Thames, I met another Bethune: a man whose passion

and foibles constantly had him falling on his ass, but a man who every time he

fell, wiped off the dust and insisted on trying again. The best, or at least the

biggest example of this was the model hospital in China. Bethune insisted that

the Mao's guerrilla army build a model hospital. He insisted that this was the

only way he could train the Chinese in modern medical methods. And so the guerrilla

army pored enormous energy and effort into the construction of a model hospital.

The partisans took a tremendous pride in this accomplishment. However, within

three week of it completion, just as the Chinese had predicted, it was destroyed

by the Japanese. Now this was a catastrophe that Bethune did not cast off lightly.

He was devastated. But he learned from it, and used it as a spring board for his

great accomplishments in China, and not least for remolding himself. I believe

Bethune developed a receptivity and sensitivity out of this passage. This man,

a man wrestling with his weaknesses, is a man that I can try to use as a model.

At the end of May, 1937,

Bethune was sent home from Spain, publicly a hero, privately humiliated.

"Spain

is a scar on my heart!" Bethune wrote to his ex-wife, Frances.

Ted

sometimes wondered whether he had betrayed Beth, but I think Ted just played in

earnest the part Bethune had given him: he was Bethune's Political Commisar and,

ultimately, Beth's return to Canada was in Beth's best interest and the best interest

of the antifascist cause.

Gerda

Taro

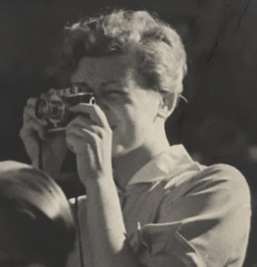

"Written

July 22, 1969. Putney, London. I sit here waiting for interruptions..." Looking

out at the river Thames. Ted's third story flat overlooked the grey river, through

a north facing studio window that reached from the ceiling almost to the floor.

No interuptions came, so Ted continued. "...

Hot sun. Madrid. July 22, 1937, Thirty-two years to the day. She was twenty-seven

and looked younger. I thought she was my age. I was twenty-one and looked older.

She was pretty. I wasn't sure about me. She was a photographer  for

the Parisian newspaper, Ce Soir, and her work had been featured in Life Magazine.

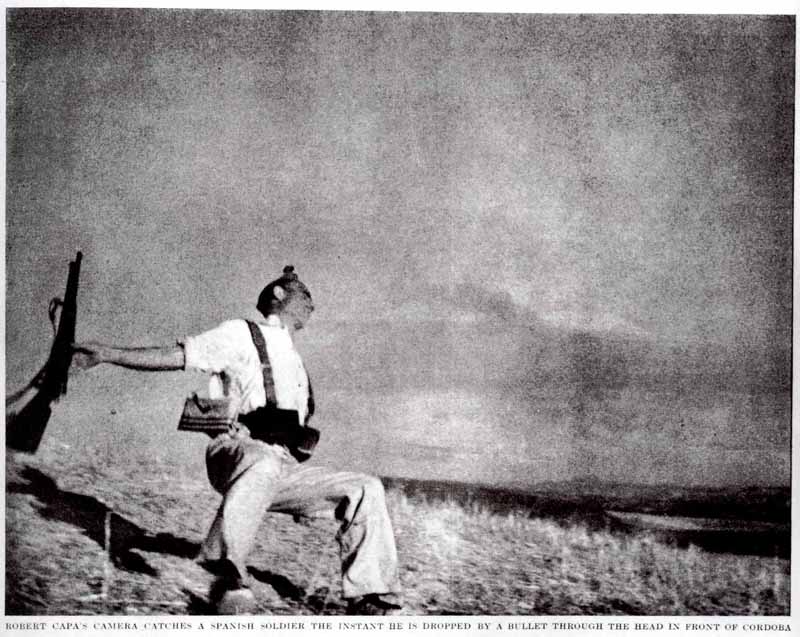

The man she was with was also a photographer, already famous: black-eyed, handsome

Robert Capa. His photograph of a loyalist soldier- just hit, falling, caught in

the act of dying, his dropped rifle still in the air - was already a symbol of

war. Gerda, Capa and myself had become good friends. When Capa returned to Paris

on business he said to me in his heavy Hungarian accent, "I leave Gerda in

your charge, Teddie. Take good care of her." I was flattered. for

the Parisian newspaper, Ce Soir, and her work had been featured in Life Magazine.

The man she was with was also a photographer, already famous: black-eyed, handsome

Robert Capa. His photograph of a loyalist soldier- just hit, falling, caught in

the act of dying, his dropped rifle still in the air - was already a symbol of

war. Gerda, Capa and myself had become good friends. When Capa returned to Paris

on business he said to me in his heavy Hungarian accent, "I leave Gerda in

your charge, Teddie. Take good care of her." I was flattered.

For

three to four weeks Gerda and I spent mornings, afternoons and evenings together

chasing stories of interest  -

battlefields, orphanages, women lining up for bread. Driving to or from the front

we would sing. She taught me many songs; "die Moorsoldatan", "Freihejt!".

Her favourite song was "Los Quatros Generalis" in which we laughed at

the four insurgent generals and praised the spirit of Madrid's resistance. Gerda

was always joyful, always laughing. For three or four weeks, we were constant

companions. And finally, one afternoon, we ended up in her hotel room. -

battlefields, orphanages, women lining up for bread. Driving to or from the front

we would sing. She taught me many songs; "die Moorsoldatan", "Freihejt!".

Her favourite song was "Los Quatros Generalis" in which we laughed at

the four insurgent generals and praised the spirit of Madrid's resistance. Gerda

was always joyful, always laughing. For three or four weeks, we were constant

companions. And finally, one afternoon, we ended up in her hotel room.

An

afternoon in late July. The twenty-second. A Tuesday. I had brought Gerda my short

stories to read. I sat on a chair trying to look unconcerned. She read slowly.

Finally she looked up. "You're good," she said. I felt dizzy.

She

walked to the bathroom, slipped off her shirt and skirt, undressing to her underwear.

She returned to the room brushing her teeth, seemingly unaware of her state of

undress. She wandered back to the bathroom to rinse her mouth, and ambled back

into the room again.

"Your very good,"

she repeated, staring at me. I tried not to look at her bra or panties.

She

lay down on the bed. I sat in my chair.

"Do

you feel like taking a nap before we go to dinner?" she asked.

I

moved to the bed, removed my shoes, and lay beside her, making sure our bodies

did not touch. I lay there stiffly and watched the ceiling. She turned and touched

my right eye-lid with her finger tip. "A man shouldn't have such eyes."

I thought she meant I had woman's eyes.

She

touched my cheek, then lay back and burst out, "I'm not going to fall in

love again! It's too painful." She sounded irritated.

"What

do you mean?"

"I loved someone. A

boy in Prague. Killed by the Nazi. It's too painful." She took a deep breath.

"You don't love Capa?" I asked, puzzled.

"I do love Capa, but not the way I loved Georg.

I don't want to love anybody like I loved Georg. Capa is my friend, my copain."

She looked at the ceiling. I studied her small nose

and perfect mouth, her golden-red hair. Our bodies still were not touching. I

moved away from her quickly when my hip touched hers. I tried not to move or make

a sound. I hadn't understood what she was saying. I didn't understand anything

that afternoon. We lay like that for many long seconds. Then she placed her hand

on my stomach, looked at me with a serious expression, and moved her hand to my

thigh, near my groin.

"Do you like being

touched here?"

I nodded, quickly, twice.

I held my breath. She took my hand and placed it in her groin. "I like to

be touched there too."

I caressed her gently,

carefully, hardly moving. Then I withdrew my hand and stared at the ceiling again.

We lay there, neither of us moving. "She's

Capa's girl," I thought. "He placed her in my charge." We had been

dear friends for a month now, she and I. I wondered if it might be alright to

turn and gently kiss her on the cheek like a friend, but I didn't dare.

She

turned on her side and studied me. "You're incredible," she said. She

sat up. "I'd better dress." She looked at me, touched my cheek, bent

down and kissed my forehead, smiling a smile I did not understand. She kept glancing

at me.

"Why is she looking so sad?"

I asked myself

She got out of bed and started

dressing. I lay still on the bed, numb.

She

finished dressing. I put on my shoes, and sat there. "Are you going to marry

Capa?"

She shook her head. "I told

you, he's my copain, not my lover. He still wants us to marry, but I don't want

to."

I sat on the edge of the bed unable

to move. She stood in front of me. I felt like crying, and smiled to hide it.

She touched my head. I said, "He acts like you are lovers. He put you in

my charge. He asked me to take care of you."

She

sighed. "Yes. He was clever. He saw how I looked at you."

I

heard myself saying, "My mother will love you."

"I

don't want to live in Montreal," she answered. "We'll live in New York."

We said no more, but went to dinner.

I

think I was in shock.

Capa wired from Paris that he might have to travel

to China. Gerda thought she might visit him in Paris before he left. Maybe she

would go to China with him. Maybe I would join her in Paris before she left or

when she got back. Nothing was settled. Everything was possible. Sunday

morning, July 27, 1937, the sun burst through my window and woke me up before

Gerda phoned. I could hear the Madrilenos going to work. Women carrying baskets

hurried to get a good place in the food queues. The morning papers lay on my bed

and I read that there had been heavy fighting yesterday near Brunete. The village

of Brunete had been entered twice by the fascists and retaken twice by our troops.

The situation was in flux.

The telephone rang.

Gerda had arranged to have a car take her to the front at Brunete. Did I want

to come?

Gerda was waiting beside the car. She

wore khaki overalls and her reddish hair was all over the place.

The

driver was French. He could speak American, not English. "Okeedokee"

was the word he knew. The sun became stronger and the car became hotter. "Let's

sing," sang Gerda. "Okeedokee," sang our chauffeur.

We

sang songs in many languages till we got tired of singing.

Gerda

stretched her arms and yawned happily. "Well, I must get some good pictures

to take to Paris. If they are still fighting near Brunete it will be my chance

to get some action pictures."

"Let's

not go too close," I said.

"How do

you want me to take pictures? Long distance?"

"That's

an idea."

"Are you frightened?"

"Yes. Aren't you?"

She

laughed. "Yes."

The chauffeur brought

the car to a stop near Brunete. "Okay, there!" he said pointing towards

the village. We walked though a rolling wheat field. Everything was strangely

quite.

"Where are the lines?" I asked.

"Right in front. In the back of the hill,"

Gerda answered. She had an instinct for such matters.

"That's

close," I said.

"That's good,"

said she.

The General, with a few of his adjutants

in tow, was walking towards his dugout. General Walters: we had interviewed him

the week before. He did not seem glad to see us now. "Of all days to come,"

he groaned. "You must go away immediately. Go back. Go right back!"

He stepped forward right into my face. "Get her away from here."

"What!" she complained. "I am going

to Paris tomorrow. This is my last chance. I must stay!"

"No!"

the General yelled. "Take her away from here. Go immediately. I can't be

responsible for you. In five minutes there will be hell!" Then General Walker

dismissed us from his attention, and marched off to his headquarters.

"Come,"

I said.

"You can go. I'm staying."

"But the General said..."

"To

hell with the General." She was adamant.

"Okay,"

I conceded, "okay. You're crazy. Let's find some cover. There are some dugouts

on the hillside there."

We snuggled into

a hole barely big enough to hide our two asses. We waited, looked around. Other

soldiers were precariously dug in around us. Then we heard the drone of planes.

We could see a flight, like geese, perhaps twelve bombers in formation. You could

see the tiny pursuit planes flying like flies around the bombers. Their drone

became louder, became a roar. They moved so slowly, one felt they might stop in

mid-air. They didn't stop. They disgorged their shit on us. The bombs fell so

quickly. Then it thundered, black clouds billowing, about a hundred yards in front

of us. It thundered again and again.

Gerda was

busy taking pictures. I was trying to see what I could use to dig the hole deeper,

while the thunder roared and the earth showered around us.

"Put

your head down!" she yelled at me.

"Where'll

I put it? I can't put it into my chest."

"Put

it down! Put it down!"

I don't think I

can find words to fit the confusion and the fear, dirt, dust, the acrid smoke.

And then the air cleared. The stuttering drone of the planes became dimmer.

"Are you all right?" I asked.

"Who

me? Sure. You?"

"Sure."

Heads began to appear from the foxholes, soldiers,

some grinning, some grim. But all to soon the planes returned. Their drone grew

again to a roar. In relays they bombed the government lines, bombed us for an

hour or more. Meanwhile the artillery shell came too without interruption. It

was three o'clock when the bombardment had started. Now, an eternity later, it

was suddenly quiet. Gerda asked me the time. "Four."

We

must have looked ludicrous trying to hide in that shallow hole. I'm sure my head

and ass showed above the ground. Gerda somehow managed to get her feet underneath

mine, but that was little protection.

"If

they come again you had better watch your head," she said. "Shrapnel,

you know."

"I know. But you're taking

pictures and your head is above the ground."

"Yes,

but I must take pictures and you don't have to."

Again

we heard the drone of aircraft, this time, though, with a different timbre. A

flight of bi-planes flying low swung towards the road not far behind us. Gerda

clicked her Leica.

The first plane turned on

its side and bellied in low. We heard the rat-tat-tat of machine gun fire. One

by one the bi-planes strafed us, nine planes in all, and with barely an interruption

the first came back to make a second pass. Then the bombers came and bombed the

lines again, and still the artillery shells fell round us. "It must end sometime,"

I said to break out of my shock. Gerda didn't answer. She took pictures of the

smoke and black earth which heaved with each bomb. She took pictures of the dust

and white smoke which came from the shells. She took picture after picture, and

I crouched there.

Suddenly she said with urgency,

"Scheise! Put your head down." The planes swung right at us. They must

have seen her camera flashing in the sun. It had become personal. We were their

specific target. The lead plane came gently towards us. There was a surge to the

sound of its engine, and a stuttering flashing through the propellers, and the

earth in front of our foxhole jumped in spurts. Gerda, unshaken, took pictures

of the planes as they came down on and over us.

"Yesus,

the roll is finished." She rolled on to her back, and started to change films.

The planes roared over just a few yards above us. Gerda's movie camera, in its

leather case, lay just beside the foxhole I grabbed for the movie camera and held

it above her head to protect her from the machine gun bullets. "Don't be

silly," she hissed. "I may lose my film." But the earth from the

strafing flew all over us, splattering us, and she allowed me to continue holding

the camera over her head..

I wanted something

to protect my face. I grabbed a clod of earth and held it on my head. I heard

a suppressed giggle. Gerda's body was shaking. "If you could only see yourself,"

she laughed.

The nightmare continued: bombs,

machine-guns, shells. Cacophony. At about half past five, suddenly on the slope

in front of us we saw men running back towards us. They were retreating all up

and down the line. If that were possible, it seemed the bombardment intensified.

We saw men blown into the air, just like in the movies, but real, just there in

front of us. You could touch it. Gerda put another roll into her Leica and rolled

over to shoot the onrushing retreat. I felt desperate. I didn't know what was

more maddening then, the planes or her camera.

One

section of the lines was orderly and the retreat went comparatively smoothly.

But a retreat is a retreat, and even though it was not a rout, there was confusion.

Men get panicky and run anywhere as long as they run. In front of us a few took

position with there guns pointed back towards the enemy, and seemed to dare anyone

to pass them. This stopped the panic. The lines reformed.

"Come,

for godsakes," I pleaded.

"Not now

while the planes are still strafing. It would be silly to go now. It will be quiet

soon. And anyways, I have one roll left."

It

was quiet. Very quiet. Here and there a figure moved. A cool breeze came down

from the mountains. The wheat swayed gently.Above the hills clouds puffed and

drifted by in a azure sky. The countryside looked serene.

"Come,

lets go," she said abruptly.

"What?"

"Yes, I'm tired."

We

got out of our rut, our foxhole. We walked back through a meadow away from the

front. The division's doctor, a blond haired man in a bloodied uniform, overtook

us. He looked worn out. All his equipment had been lost in the retreat. We spoke

in English, he with a Scottish accent, as we walked through the fields towards

Villanueva de la Canada. The lines had reformed between the two villages, Brunete

and Villanueva. We joined and followed the road. Beside the road lay the dead

and wounded. Some groaned and begged for water. Some lay silent. Gerda had no

more film.

The planes came again. We flung ourselves

underneath an overturned truck. But the planes passed over. They weren't looking

for us.

We reached Villanueva de la Canada.

It stank.Two men were sitting beside a wounded comrade.

"Please

come. Our friend is badly hurt."

The doctor

was tired. "I've got nothing. Nothing. No bandages. Nothing."

"Please

look at him."

The doctor went over to the

wounded soldier and lifted the blanket. The legs looked as if they had gone through

a meat-grinder. The man made no sound.

A tank

passed - one of ours, of course - we stopped it, and put the wounded man on it,

and then jumped on ourselves. There were four tanks behind us. Clumsy looking

animals. Some planes came flying over again. They dived. Tat-tat-tat-tat.

"Silly getting killed now after going through

what we did."

"Bah,

they can't hit a thing," said Gerda.

The

tank was hot. It snorted and wheezed, made lots of noises, and swung from side

to side. We held on tightly.

A white house beyond

Villanueva served as a dressing station. We took the wounded man off the tank.

The doctor found a car, and rushed away to get ambulances. Not rational, that.

Anyone could have gone on that errand, and he could have stayed with the wounded.

The wounded were dragging themselves, or being carried, to the dressing station.

The five tanks we had come with had stopped right beside the medical station.

That was silly. A marvellous target for planes.

"Got

the camera?" Gerda asked.

"Yes."

A large black touring car came down the road. We

stopped it and asked for a lift as far as El Escorial.

"Sure,

get on."

We jumped on the running board.

"Gerda, you go on the other side."

"Why? It is big enough. We can both stay here."

She put her cameras on the front seat of the car.

There were three wounded men inside. "Salud."

"Salud."

She took a deep breath. "Boy, that was a day.

I feel good. The lines reformed. I got wonderful pictures. And you? You have a

good story, yes?" she shouted above the wind.

"Yes,

but next time I cover the war from the press office. I can describe it better

in comfort."

"Tonight we'll have a

farewell party in Madrid. I've bought some champaigne. Then perhaps we'll see

each other in Paris. In any event, I am going to China with Capa soon."

"I'd like to go to China too," I said.

There was some confusion ahead of us. A tank was

approaching. It had been strafed by a Nationalist plane and was driving irratically

weaving across the road. Our car swung to the left to avoid it. "Hold on,"

Gerda laughed.

The car went out of control; began to roll. Then I was on the

road. Then I knew that both my legs were off. Then I knew they weren't. I saw

blood on my right leg. And the pants torn on my left. There was no pain.

"Gerda!"

Two soldiers ran towards me and dragged me towards

a ditch.

"Donde esta mujere! Mujere! Mujere!"

Then I saw her. I saw her face. Just her face. The

rest of her body was hidden by the overturned car. She was screaming. Her eyes

looked at me and asked me to help her. But I could not move. There was no pain,

but I could not move.

The tank was quiet now.

It had swung around and now it was quiet. The young Spanish driver looked at us.

He was frightened.

The planes came. The man

beside me dropped down to huddle in the ditch. The other pulled me into the ditch.

Everyone ran for the fields.

"Gerda! Where

are you? Gerda."

The planes went by.

"Donde esta mujere?"

"She's

been put into an ambulance," someone told me.

"Are

you sure? Es Verdad?"

"Si si."

"And her camera? Where is her camera?"

"Yo no sai."

Someone

brought me a brown cloth belt. It was crumpled and the wooden buckle was broken

into little pieces. "It is hers," said the someone.

"Where

is the car?" I asked.

"Yo no sai."

Then I began to feel the pain. "Agua. Water,

I need water." But no one had water.

They

put me on a stretcher and placed me in an ambulance.

There

was no water.

The pain became heavier. I held

the brown belt in my hands.

We stopped at a

dressing station. "Did they bring a woman here, a small pretty woman with

reddish hair?"

"Woman? There was no

woman."

They gave me water. I looked at

my watch. It read six-thirty. I put it to my ear, but it did not tick. It had

stopped. "Six-thirty. That's when we were hit."

"What?"

said the man beside me.

"Nada. Como esta?"

How are you?

"Just a machine-gun bullet

in the thigh," he said.

It was growing

dark. I still held the belt in my hand. It was becoming wet from sweat. At some

point I fainted or slept. I remember someone slapping me awake. Then the hospital

at El Escorial. It was an English run hospital. I asked if they had seen a woman,

a red haired...

"Yes. Gerda Taro. Yes.

She's here. They brought her here some hours ago."

"How

is she?"

"She's all right."

"Can I see her?"

"No.

She's just had an operation. You can't see her."

They

injected anti-tetanus into my arm and marked a cross on my forehead.

"Will

I be able to see her in the morning?"

"Yes."

"How is she?"

The

English nurse smiled at me. "She's all right. She's suffering from shock

but I believe she'll be all right."

"She

needed an operation?"

"Naturally.

Why do you think we gave her one?"

"I

don't know."

A Dr. Caldwell came over to

my stretcher. "How do you feel?" he asked.

"Good.

Can I see Gerda?"

"No, I'm afraid

not. She's suffering from shock. It would be bad for her if you saw her."

"But I might be good for her. I love her. I

want to marry her."

"It would not

be good for her," he said, his mouth tightening. He told me that when she

had been brought in she had asked to send a cable to Paris, to Ce Soir and to

Capa. He had done that.

The wounded lay on the

floor of the hospital. All the beds were taken. The ambulances kept unloading.

My pain became worse. Dr. Caldwell gave me a shot

of morphine. "There. Now you'll go to sleep."

"Does

she say anything?"

"Well, she asked

for her camera and I told her I hadn't seen it. When I told her you were here

and were all right, she told me to give you her regards."

My watch

still showed six-thirty. I asked the time. Three-thirty. I couldn't sleep.

All night the wounded came. The doctors worked smoothly,

quickly in their triage. Here, this one, cut free the clothes. Fracture? Abdomen?

Bullet wound. Bring him to the theatre. This one's dead? Take him away. All through

the night.

"What time is it?"

"Five a.m. Why don't you sleep?"

"I

can't sleep. Can I see her now?"

"No."

Well I would see her soon. We would joke about the

fact that we had been hit by our own tank after missing all those shells and bombs.

And she would probably raise a fuss about losing her camera. She'd probably insist

we go back to look for it. It might still be in the car. No, we probably couldn't

go ourselves. We'd have to send someone. At

five-thirty Dr. Caldwell came to my stretcher. "Well, I think everything

looks much better. We just gave her a blood transfusion and she said 'Whee, I

feel good.' She asked about her camera again, and when I told her it was lost

she said 'C'est la querre.' She's swell."

"Can

I see her now?"

"For godsakes, man,

not now. She must sleep now. If she sleeps everything will be all right. You'll

see her later."

I drank some coffee. I

was still holding the cloth-woven belt in my hand, fingering the remnants of the

fractured wooden buckle. It was crushed, shattered. I tried not to think what

that might mean. "I'll try and sleep now," I said to myself. "I

suppose this is a good story."

Dr. Caldwell

walked towards me. "I'm afraid I have bad news for you." I knew what

he was going to tell me. "Gerda just died."

"Give

me a cigarette," I said.

He lit and handed me a cigarette. He turned

and came back with a hypodermic needle.

"No.

I don't need it. For Chrissake, I don't need it. When I need it I'll ask for it.

I feel no pain."

"You're going to

need it." He jabbed the needle into my upper arm.

I

wanted to ask if he was sure she was dead, but I didn't. I wanted to go to sleep

and forget. I could not.

A nurse came over

and told the doctor about another case, and he had to leave. "Would you like

to be taken into my room?" he asked me.

"Please,

if you can."

An antiaircraft gun began

to fire. The shutters rattled. Caldwell came back. "You'll never know how

sorry I am I didn't let you see her. But I didn't know. I really thought she would

recover."

"Oh, hell. That's all right."

"If you want," he paused. "If you

want you can see her now."

"Hell,

I don't want to see her now." But I did. I didn't believe she was dead.

They brought me upstairs on a stretcher, and I looked

at her, and her face was not quite the same.

Then

they carried me down and I kept slipping on the stretcher, and the boys carrying

me told me to hold on or I might fall. They put me in Dr. Caldwell's room.

Someone had an English cigarette and gave it to

me. The smoke curled. Then a nurse brought me Gerda's cigarette case. There was

one cigarette left. I put out the English cigarette and smoked the one in Gerda's

case. It was a Spanish cigarette, and I never liked Spanish cigarettes. The doctor

asked what I wanted to do with her body and I wanted to tell him to go to hell,

but he meant well, and I asked if he could arrange to get it to Paris. He said

he would.

Then the nurse came over and

said that she was sorry.

Ted

wrote the story of his involvement with Gerda soon after her death. Then for the

next twenty years he largely forgot her. In many ways his heart froze. Twenty

years later, in the '50s he fell in love with a young red-headed woman who used

the same mixture of two French perfumes. Soon memories of Gerda came flooding

back in dramatic fashion.

…

we were flying over the English Channel in the belly of a freight-plane, an air-ferry

which transported motor cars. I suddenly started choking. I had the illusion that

I was inside a military tank. I started to talk to Lucille in Spanish, asking

her if she was alright. It frightened her. It frightened me.

At

the British Customs in Folkstone Lucille went off for a moment to the bathroom

and I became frantic. I asked the Customs Officer in his strange uniform, I asked

him in Spanish, "Donde esta la mujere con pelo rojo?" The puzzled Custom

official asked, "What?" and then Lucille appeared, looking pale and

anxious. I kept asking her, "Are you alright? Are you hurt?"

"I'm

fine," she mumbled. "Are you alright?"

This

was the first evidence of my amnesia lifting.

That

night, back home on Sandy Road, by Hampstead Heath, I became conscious that I

was sitting on my kitchen floor, banging the floor with my fists, sobbing and

screaming, "You're not dead! You're not dead! You're not dead!"

Lucille ran downstairs from our bedroom petrified,

the blood blanched from her face. We didn't sleep that night.

After

this we frequently find musings on Gerda in Ted's notes.

Notes

dated August Tuesday 1985:…

"Reading Whelan's book on

Capa and getting confirmation about my conversation with Gerda, the "Capa

and I are not lovers. We are copains, comrades."

According

to Whelan, all their friends knew this, but Capa didn't like it. He wanted to

continue the relationship as lovers, but she didn't want it. She was falling in

love with me, and kept saying, "I won't fall in love again." Undated

notes:

"Gerda was

laughing and making terrible sounding noises and spitting. She was mimicking my

cigarette cough. At first I had no idea why she was making such nasty noises.

"Because," she laughed, "that's what you sound like!"

I couldn't believe that. How could I sound like

that? I had no idea I coughed and spat so unpleasant. But she wasn't angry with

me. She just laughed.

Then we were holding each

other and she was telling me that a man shouldn't have such eyes. "I do not,"

I replied, "have a woman's eyes."

"You

are a total idiot," she said, and laughed again.

I

loved to hear her laugh.

Notes

dated "Toronto, July 19, 1990":

"Rereading

what I had written a month or so after she'd been killed, I got very tired. There

are things I left out. Did she really say she might be going to China with Capa?